Ashlee is a veteran teacher at a Title 1 elementary school. Despite the many challenges her students experience, her students meet or exceed grade-level growth goals. She holds a master's degree in curriculum and instruction, is consistently rated as a highly effective teacher, and has received a county "outstanding educator" award. She is compassionate. Kind. Creative. Intelligent.

And she's burning out—considering each day whether she wants to stay in education.

She also happens to be my wife.

I travel and present to educators all over the world about educator burnout, highlighting the research-based strategies that have helped me and tens of thousands of educators strengthen their well-being.

So why is my wife—a phenomenal teacher—burning out? She has access to a guy who can cite and teach ad nauseam the strategies that lead to increased gratitude, purpose, and joy. I can do a deep dive on why exercise, mindfulness, and forgiveness boost our physical and emotional health. I can help her spot every cognitive distortion that arises and smite it with a research-based reframe. But it's not enough. Because burnout isn't about the individual—it's about the organization. It is an issue of context, not character.

My wife is a testament to how educators and school leaders—myself included—have misunderstood burnout, placing the onus on teachers via "self-care solutions." If we really want to reduce burnout, though, it will take more than exercise routines, meditation apps, and free donuts in the staff lounge. More than cognitive reframes and mindfulness strategies. Much more.

Let's start with a better understanding of what leads to teacher burnout.

The Computer Analogy

For perspective, it's helpful to consider teacher burnout through the lens of a computer (see fig. 1), a concept I explore in greater depth in my forthcoming ASCD book, a guide for school leaders on reducing staff burnout and increasing retention. Obligatory caveat that teachers—humans—are much more complicated than computers (and can't be replaced by them). But this analogy helps us understand the many factors that play into a burned-out teacher.

Figure 1. The Computer Analogy of Staff Well-Being

The Charger: Self-Care Strategies

One of the first efforts school leaders use to support staff well-being is promoting self-care. Exercise competitions, meditation websites, wellness workshops. This seems like the logical move: The teacher is burning out, so fix the teacher. But asking teachers to fix their burnout is like asking a seed to grow better when the soil is dry and the sun is nowhere to be found.

Of course, we shouldn't ignore the importance of self-care: Educators benefit when they use research-based practices to improve their well-being (Mielke, 2019). We need energy and motivation just to "turn on" our skills.

However, self-care is like the charger and battery of a computer: A teacher can practice all the self-care strategies in the world—be fully charged—but energy will be zapped if the hardware is damaged or too much software is running simultaneously. Our experience with holiday and summer breaks points to this: If we recharge when we're away from work but quickly lose energy without another break on the horizon (think "February Funk"), then working conditions are driving burnout—not a lack of self-care strategies. Put differently, we have to address the systems, policies, and conditions that "drain batteries" so quickly and reliably. We have to look at the software and hardware.

Software: Curricula, Programs, Initiatives, Expectations

Running too much software at once is a surefire way to crash or slow a computer. If we want to avoid draining the battery on our computers or phones, we close out programs we're not using—or even delete the ones that are no longer serving a purpose. We also know that the fewer programs we have running, the better the performance on each one—whether we're talking about computers or educators. The key questions school leaders should ask are: How many programs are we running at a time? How inefficient are our systems because we're running too much at once?

Work overload is the biggest cause of emotional exhaustion, the first major dimension of burnout (Maslach & Leiter, 2014). I've seen this process unfold with my wife. She recently showed me all the scripted curriculum guides she has to use in her elementary school—seven in total, three brand new. Her day is mapped out nearly to the minute, with a note from administration reading, "You won't have time for a scheduled snack, so try to build one in with your students while they work." In my wife's words, "I feel like I have no time to do the things that made me love teaching."

Unfortunately, too many schools try to fix problems by doing more with more, rather than more with less.

Hardware: Efficacy, Skills, Strengths

OK, maybe you have to run a few initiatives at the same time to try to make gains. If so, you'll need to boost the hardware to keep up with the energy and focus demands. Just as improving computer hardware takes more time and expense than adding software and programs, improving the hardware of educators is a deeper commitment. It takes high-quality coaching, feedback, and positive support.

Along with emotional exhaustion, inefficacy is another major dimension of burnout (Maslach & Leiter, 2014). Building efficacy requires more than confidence-boosting mantras like, "You got this!" and "We value you!" It requires mastery experiences: Competence attained through high-quality professional development and timely, constructive feedback in safe, supportive environments. If we want teachers to persevere through challenges, we need to create conditions that build efficacy: that involves coaching, time, and support.

WIFI: Human Relationships, Connectedness

Just as we value technology to connect to the outside world—to learn, to transmit, to bond—high-quality teaching requires connection. And this means authentic, positive human relationships between every stakeholder—staff, administration, students, and community members. Cynicism (often called "depersonalization") is the third and final dimension of burnout (Maslach & Leiter, 2014). It involves negativity and pessimism, particularly involving people. Education is a highly social endeavor; when relationships are strained or cultures are toxic, the whole system suffers. Of course, we can use computers without WIFI, but our work and access might be impeded. Similarly, teachers can teach without strong connections, but their motivation and performance are vastly diminished.

Troubleshooting the System Failures

When a computer is broken, we look beyond just its battery or the charger to diagnose and resolve the issues. Likewise, let's look beyond self-care strategies to reduce teacher burnout and increase retention. Here are a few key moves school leaders can make.

Tip #1: Run System Diagnostics

The most important place to start with burnout is assessing its causes. Engage a "curiosity mindset" and seek a better sense of what's driving burnout: Is it exhaustion from too many initiatives (software)? The need for greater skills and capacity (hardware)? A lack of opportunity to build positive connections with students and colleagues (WIFI)?

To get high-quality feedback from staff, use high-quality questions to survey staff (e.g., Don't just ask, "What's stressing you out right now?"). Thankfully, validated measures already exist for these surveys, such as Mind Garden's Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and Areas of Worklife Survey (AWS). These assessments help identify the extent of burnout within an organization and its central causes. (Here's a sample inventory to try.) Too often we use self-care as a solution because we don't know the true cause of burnout. Ask what your staff's experience is with their working conditions. Listen to their answers. Practice getting "un-defensive." And work collaboratively on ways to make your school a place where people thrive.

To help teachers to persevere through challenges, we need to create conditions that build efficacy: coaching, time, and support.

Tip #2: Reboot the CPU

If you've ever experienced a computer crashing in the middle of a project or task, you know how devastating it can be: Memory is lost, programs need to reload, or the system itself might require a massive reboot or new hardware. Educators crash whenever there is an intense threat to their safety and security. School safety threats, a screaming parent, seeing a colleague let go—all of these can cause a crash. When these things happen, prioritize the CPU.

Clear communication. Speak candidly and directly with educators in person to reduce miscommunication. For instance, if there was a recent threat to school safety, assemble your educators together and speak directly about what happened, what the next steps are, and what the school team is doing to ensure safety is a priority.

Protection. Make sure educators know they are safe and secure. If a teacher is verbally abused by a parent, for example, intervene ASAP and make sure all future communication from the parent goes through you, the school leader.

Uplifting emotions. Provide staff members individualized praise, practice gratitude, and show compassion. Write a personalized thank-you note acknowledging a teacher's resilience. If your school suffers a tragedy, check in one-on-one with as many of your staff members as possible. Lead your staff through adversities by leveraging human relatedness.

Fighting Initiative Fatigue

One of the best ways to reduce initiative fatigue is to focus on practices instead of programs.

Tip #3: Close Out Software

As a part of our school improvement process, our district took inventory of all the initiatives we've started in the last few years. The number? Forty. That's right. Forty initiatives for a school district of 150 certified teaching staff. There are diminishing returns to adding new things without freeing up time and effort to do existing things really well (something our school improvement team realized looking at our district's list). As school leaders, we should ask ourselves, are we doing too many things with mediocrity rather than a few things with excellence?

One of the best ways to reduce initiative fatigue is to focus on practices instead of programs. Before implementing any new initiative—or as you evaluate existing initiatives—work with your team on these questions:

What is the desired outcome of the program/initiative?

What 3–5 practices would we see as evidence of implementation?

What do staff members gain by implementing these practices?

What roadblocks might stall the habituation of these practices?

How will we support the initial implementation of these practices?

How will we monitor and support ongoing implementation of these practices?

Through this process, you might realize that (a) you don't need a new program, (b) you already have the skills and people necessary to achieve the desired outcome, and/or (c) previous programs aren't necessary and you can discontinue them in service of coaching—mastering existing practices rather than adopting packaged programs.

Tip #4: Invest in New Hardware

You don't have to know much about computers to know that swapping out the hardware is a big investment that takes time and expertise. It's not as simple as, say, downloading a new app. Building teacher efficacy is the same: If we want teachers to have greater skills to tackle initiatives or the challenges of teaching, we need to devote ample time and resources to help them be successful. We do this via high-quality coaching.

Skill-building requires more than sporadic check-ins with administrators during evaluations. No matter how sophisticated your current coaching systems are, look for ways to bolster them.

Create true coaching positions. Identify your top teachers and mentors—especially those interested in coaching—and give them ample support and time (more than one hour a day) to provide peer coaching. To avoid work overload, don't just give someone the responsibility of coaching without the dedicated time to do it. Consider full-time coaching positions—a possible career track for those who don't want to pursue the principalship. Build a team of coaches from within and honor coaching as more than just a "nice-to-have."

Make coaching non-evaluative. "Coaching" is a four-letter word in many schools because it is used as a response to poor evaluations. Draw a clear line in the sand that coaching roles and experiences will have nothing to do with evaluative conversations. When an administrator has concerns over a teacher's performance, bring the coach in only after the administrator and teacher have agreed upon an instructional goal. Develop policies of confidentiality between coaches and coachees.

Develop informal peer-coaching opportunities. If you can't create new roles, dedicate ample PD time for staff to help peers set goals, observe each other, and provide feedback. Use video for teachers to watch their own and each other's teaching more objectively.

Use established systems. Masters of coaching have done the heavy lifting, so rather than building a coaching system from scratch, use what works. Jim Knight's Impact Cycle (2018) is among the most powerful systems I have seen and used. It provides structured conversations, leverages objective data, and is adaptable to any school's needs. Most of all, it respects and empowers teachers—both of which are critical to improving educator well-being.

Investing in new hardware takes time and energy. However, if we invest in practices and skills—and we close out other "software" that burdens our time and energy—we help our staff develop the efficacy and skills needed to handle new challenges. We foster collaborative, confident communities. And we show our staff that we value people over programs.

Systems Built to Thrive

The past few years have challenged us beyond what self-care strategies can fix. Pandemic teaching put a strain on our efficacy and skills. Initiatives stopped, restarted, and got added to our plates as we scrambled to teach in this new era. Our connectedness took hits as distances grew physically (with remote schooling) and emotionally (with political divides).

Yet, these past few years have pushed us to help our systems work at their best. Let's also help our staff work at their best. Let's revamp our organizations to reduce the conditions of burnout. For the sake of our students. For the sake of our colleagues. For the sake of amazing teachers like my wife.

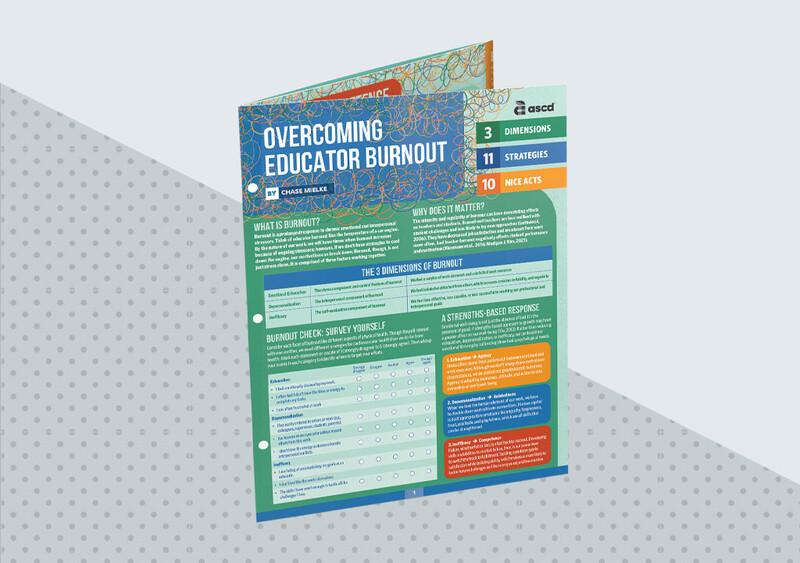

Building Educator Resilience

In his new Quick Reference Guide, Chase Mielke outlines the factors most likely to lead to burnout and how to combat them.