As 3rd graders, my students already have several years of experience with poetry.

“Bake and steak! Those rhyme,” Elijah cheers when he catches the same ending sounds. Sara claps along to the rhythm and finds that syllabication creates a magical beat.

Poetry in this way is fun—fewer words and joyful reads.

And then there’s the flip side. “What’s this supposed to mean?” they ask quizzically. Elementary students often struggle with the abstract nature of figurative language—their concrete thinking makes it challenging to grasp why "the elephant is a mountain" or how "silence shouts." This cognitive leap from literal to figurative understanding is especially difficult for young readers, whose experience with language is still developing.

As W.H. Auden says, "A poet is, before anything else, a person who is passionately in love with language.” Poets weave tapestries with word play, structure, and literary devices—and that’s precisely why students scratch their heads and say, “Huh?” Luckily, teachers can use different strategies to unlock the power of poetic language for students.

The Weight of Words

When poets use less description and more figurative language, they're often aiming to evoke emotions, create vivid imagery, or convey complex ideas in a more nuanced way. Poems have an intricate structure and use fewer words, so it's important for students to understand that every word carries weight and is selected with intention.

All year, I pause during lessons to savor how an author has played with words. “The river ran slow as syrup…” I read for a second time amidst Eve Bunting’s Secret Place. “What do you see when I read that simile?” Students build their awareness, not just of the type of language, but what it does to them as a reader.

Students build their awareness, not just of the type of language, but what it does to them as a reader.

However, I realize that students need more than the ability to hear figurative language. They need to identify, distinguish, and interpret it. One day, while working with a small group, I discovered a strategy that pulled it all together. We were "stretching" our brains by taking an existing simile and converting it to a metaphor. This switching forced them to engage differently with the content—and they enjoyed it. An idea emerged: What if I had them "play" with words this way? What if they "stretched" and thought flexibly about different kinds of figurative language?

The "Figurative Language Stretch" Strategy

"Figurative Language Stretch" progressively moves students to both read and write effective figurative language. It's a simple sheet of notebook paper with a topic at the top and various types of figurative language listed in the margin. The kids do the rest.

Step 1: Building a Foundation

First, I examine my standards for what types of figurative language students are expected to learn and gather exemplar texts. This year, I began with similes. For the mini lesson, I gather students on our "living room" carpet. I say and write: The wind howled like a wolf through the trees and tell them to take a minute to study the sentence and be ready to share what they notice.

Then I give them an opportunity to share out about not only the words but the image they create and the feelings they evoke. "Put a picture in your head,” I say. “What do you see, smell, touch, taste, or hear?" I nudge them to connect what words activated those senses.

Then I add another simile: The breeze was as gentle as butterfly wings. We complete the same process, then compare and contrast the two. When discussing differences, I make sure to talk about changes in tone. Next, we take time to reflect on the author's purpose. I ask students to consider what they want the reader to understand and feel. They share out and then jot notes about their takeaways.

Step 2: Practice and Expansion

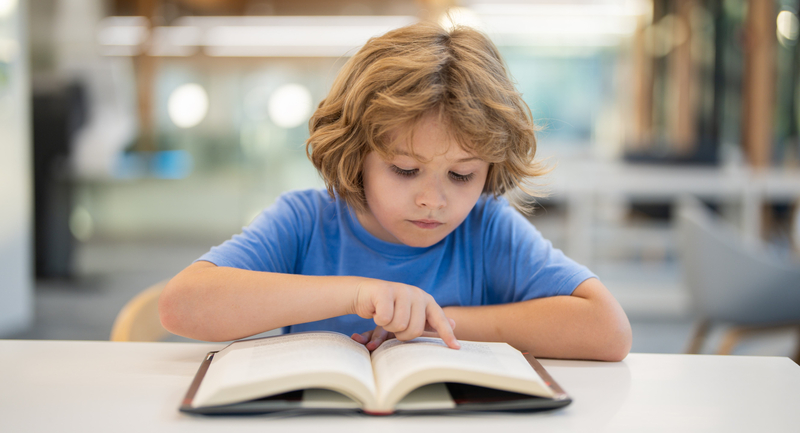

Throughout the next few days, students practice creating that particular type of figurative language (similes in this case) on their own. I provide open chunks of time for them to explore our classroom library, looking specifically for examples of how authors use similes to convey meaning and emotion. They collect these examples in their notebooks and then use them as inspiration to write their own similes about topics that interest them. When students write their own figurative language, I ensure there is time for revising based on both teacher and peer feedback.

We move through the same process with other forms: hyperbole, metaphor, onomatopoeia, and personification. As we layer in each new device, we spend time exploring how each type is unique and elicits different images and feelings in the reader. I continually ask, "Why might an author use it? How might that add to the reader's understanding of the text?"

Step 3: The Stretch

Finally, when we've introduced all types and are ready to stretch, no worksheets are necessary—just their notes from all we've explored.

I start by selecting a topic students connect with and explain that together we will create different types of figurative language using that same subject. I model using the topic "dog." For a simile, I write: The dog was as white as whipped cream. Students jump in with their suggestions, and we discuss.

Next, I write "metaphor" in the margin beneath the simile. I pause to consider and think aloud: "Dogs guard and protect...like a password!" I write, The German Shepherd was a locked password at the front door. I continue to think aloud and model how to stick to the topic while altering the sentence to reflect different types of figurative language.

Budding writers begin to play with words confidently, creating rich and engaging poems of their own.

Once students have this model, they're itching to try it on their own. Since we've been using “dog” as our example topic, many students continue with this familiar subject for their first attempt, which is perfectly fine. They work independently to create their own figurative language examples. After writing time, I have students share their work and provide time for both my feedback and peer responses.

After this initial mini lesson, Figurative Language Stretch becomes a center activity. Students choose their own topics, creating various types of figurative language themselves. The payoff? They have a resource and a host of their own figurative language examples to use in their poetry.

A Toolkit for Young Poets

Demystifying figurative language becomes a crucial piece in both unlocking poetry and serving as a springboard for writing. With this strategy in their toolkit, young readers step into the shoes of poets and learn to understand what figurative language does, why it might be used, and the effect the author intended. Beyond that, budding writers begin to play with words confidently, creating rich and engaging poems of their own.

Rooted in Reading

Effective practices for teaching reading and supporting student engagement in literacy at all grade levels.